Banns, Special Licenses, and Common Licenses in Georgian England

- Paullett Golden

- Mar 1, 2020

- 8 min read

Updated: Aug 24, 2024

Publication Date: March 1, 2020

What's your pick for the best wedding: elope to Scotland, have the banns read, or obtain a license?

The topic for this research interest section is on licenses to marriage. A special license is something we read quite often in historical romance novels, but how common was it, and would it have been used/acquired how our heroes typically do in these novels? There were three ways to marry: a traditional ceremony after the reading of the banns, elope to Scotland, or license (common license or special license). A license, be it common or special, allowed great flexibility as to how, when, and where a couple married, but it was difficult to obtain and rare, despite how often we read it in novels. While the focus of this is on the special license, I'll touch on banns, as well, to put things into perspective.

In The Earl and The Enchantress, our hero and heroine marry by special license for the sole purpose of expediting the wedding so that Lizbeth's family may begin their lengthy return trip south before the winter months affect their travel. There was no reason to rush, but had they waited for the banns to be read, it would have delayed the family's travel by an entire month, pushing them far too close to winter for safe travel.

Let's start with the banns. Prior to 1753, legally binding marriages were a bit loosey-goosey. The Marriage Act of 1753 set a legally agreed upon practice that would constitute a binding marriage, all in an attempt to avoid increasingly frequent cases of bigamy, fraud, clandestine marriages, handfasting, seduction, and forced marriages. This version of the act lasted until 1868 before it was amended. It has seen several amendments since then. This act created the most traditional method of marrying--applying to the church of residency to have the announcement of intention read prior to the marriage. This page offers a succinct description of how a traditional marriage would be approved by the church through the reading of banns.

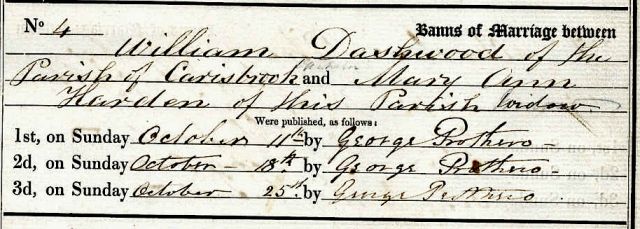

Banns of Marriage

The couple to be married would need to apply to the church cleric at least seven days before wanting the banns to be read. Banns would only be read at the church parish of residency, which had to be proven before the clergy would agree to read the banns. "Residency" meant residing for at least four weeks in that parish. If the couple resided in separate parishes, the banns would be read in both parish churches. The purpose of reading banns was to provide ample opportunity for parishioners to oppose the marriage if just impediments existed. Banns would be read three Sundays in a row to ascertain if there were any impediments to the marriage. Those wishing to file an impediment charge had those three weeks in which to act, after which time, their ability to file a charge expired. Following the successful completion of the reading, the couple could marry within the church that the banns were read within three months of the banns being read and from the hours of 8am to 12pm (the hours were expected but not put into legally binding writing until the amendment of the act in 1868).

Impediments may include, but certainly aren’t limited to:

Bigamy

Incest (parents-child, siblings, uncles/aunts-nephews/nieces)

Brothers-and-sisters-in-law (illegal to marry deceased husband’s brother or deceased wife’s sister)

Religious differences

Social class differences (including employer and servant)

Age differences

Family opposition (esp if one party was under the age of 21 and did not have express permission from parents/guardian to marry)

Pregnancy

Interracial couple

Illegitimacy

Financial or legal concerns

Existing betrothal (to someone else)

Age below 16 (for either party)

Seduction, coercion, and/or fraud

Unwilling bride

While some of the mentioned impediments were subjective (and those marrying could choose to obtain a common license to bypass the banns if necessary, such as an employer marrying a servant or a widow marrying a younger man), others could lead to legal ramifications if the marriage followed through. Depending on the charge, the marriage would either be void or voidable. Void would mean the marriage would be completely erased from history and not recognized as ever having existed in the first place. Voidable would mean the marriage could be annulled on the basis of the charge, but an annulment does recognize that the marriage did take place and was merely dissolved after having taken place. There were other outcomes than void or voidable, of course, such as if bigamy was discovered, which was a crime and came with a hefty fine, jail time, and social ostracization.

Hence, the importance of banns! This time of asking was crucial to avoid any future legal ramifications.

A great read on marriages of the era: https://jasna.org/publications-2/persuasions-online/vol36no1/bailey

Why were marriage rules put into place? Read this to find out about the Campbell scandal that forced the hands of the court to finally make a marriage law--scandalous!

The calling of banns read thus:

"I publish the banns of marriage between [bride or groom name] of the Parish of [name] and [bride or groom name] of this Parish. This is the [first, second, or third] time of asking. If any of you know cause or just impediment why these two persons should not be joined together in Holy Matrimony, ye are to declare it."

This traditional method served as the engagement announcement--announcements were not printed in newspapers as they are today. The only formal announcement made was the reading of the banns. So what about those who needed to expedite the process? Let's look at the two different types of licenses: common vs special. As popular as the special licenses are in historical romances, let it be known that it was extremely rare in reality--only six cases in 1730 and twenty-two cases in 1830, for example. The common license was issued at approximately 2,700 per year. This page offers a thorough explanation of the differences in licenses, which I'll attempt to capture concisely here:

A common license is something we don't often read about in historical romances for some reason, but it is one of the two types of licenses a couple could obtain to bypass the calling of the banns and was the more popular of the two types of licenses. To obtain such a license, the groom (or someone on his behalf) would need to apply (yes, a formal application that would be filed as a legal record) to the bishop of the diocese (or in his absence, granted by his chancellor or the rural dean) with the following: a license fee of 5-10 shillings (depending on taxes), a sworn affidavit that there was no impediment, a promissory bond of a substantial amount (£40 to £200) in the event an impediment arises (which also required two witnesses that swore the groom could pay the amount and second bondsman who swore to pay the bond if the groom was unable), and the permission of the parents/guardians (unless the bride was over 21 years of age). This common license allowed for the couple to be married immediately, but they still had to marry within the residential parish church (residential as in at least four weeks of residence) during the hours of 8am-12pm and with two witnesses. They had three calendar months in which to marry after obtaining the common license. The license was nothing more than permission to marry without banns being read and did not constitute a contract of marriage in and of itself. The records of the bonds and affidavits are still available to view, interestingly, from as far back as 1597.

If you clicked on the link I provided above, you'll have seen the list of some of the most common reasons a couple obtained a common license. The list is interesting, don't you think? Things like a master marrying a servant, the parties being of different religions, the family opposing the marriage, etc.

A special license needed to be obtained from the Archbishop of Canterbury, located in London--Knightrider Street, Doctors' Commons, near St. Paul's Cathedral. It also required a sworn statement of no impediment and the permission of parents/guardians (for brides under 21) and cost approximately £30 (while that would equal about £2500 in today's currency, let it be made clear that the annual family income was approximately £30, so imagine paying a tad more than an entire year's worth of income for this permission slip). (This page is a quick and dirty chart of wages to put things into perspective, and this page offers a quick look at cost of living vs annual income.) Another complication of the special license aside from cost was that the applicant had to persuade convincingly the need for the special license over banns or common license. Further still, the only people who could obtain the license were nobility and their children, baronets (but not their children), knights (but not their children), Members of Parliament, and select government officials. Gentry or otherwise could not obtain this license. There is a brief stretch of time wherein gentry or otherwise could have, but it was a small window immediately following the Marriage Act of 1753 until 1756 due to the unclear wording within the act on who could obtain the license. The wording was corrected to avoid further misinterpretation. It's not surprising to learn the number special licenses requested tripled during that little window of opportunity.

The significant difference between this license and the common license is that the special license allowed the couple to marry wherever and whenever, meaning not within a church (outdoors? family parlor? anywhere!), within any church of their choosing, and anytime outside of that 8am-12pm requirement (a wedding beneath the stars, perhaps?). If you compare the differences between the two, there's no clear reason why couples wouldn't get the common license instead of the special license unless they objected to marrying within a church, within their church of residence, and/or within the 8-12 hours. The common license was affordable and locally available. The special license was incredibly expensive for the time and only available in London at the Doctors' Commons by the Archbishop of Canterbury. Granted, it did not require the same set of witnesses or promissory bond as the common license, but that was really because the groom paid in cash with his £30 not to require those.

Given this knowledge, we should see a rash of common licenses in historical romance novels rather than the special license. The popularity of the special license is quite the mystery, especially given its rarity and cost with no additional benefit other than marrying outside of a church and outside of a given time (however romantic it is to marry in the family parlor, is it worth several thousand in cash?). It would not have been popular amongst our aristocratic heroes and certainly not available to our gentry heroes. In the case of The Earl and The Enchantress, this shows how deep are Sebastian's issues with the church, for he preferred to ride all the way from Northumberland to London and back to obtain a special license that would allow him to marry Lizbeth on a cliff side rather than simply obtain a common license from the local bishop and marry within the parish church. It tells us more about his character than it does about the time period. Or, I suppose, we could simply say he was a hopeless romantic who preferred the seaside to the church. Wink.

For a more thorough discussion of marriage laws, including things like divorce, check out this post by the Jane Austen Society of North America.